Comparative Education Experience in Cuba

What does school look like in Cuba? Thomas Timar, professor of education and faculty director of the Center for Applied Policy in Education (CAP-Ed), designed a UC Davis Quarter Abroad program in conjunction with Cuban instructors to demonstrate a hands-on comparison of Cuban and American education systems. Literature, language, arts and culture, and Cuban classroom visits were incorporated into the students’ experience at Casa de las Américas of Havana during Spring Quarter 2010.

According to Timar, UC Davis is one of very few universities in the United States licensed to have an educational program in Cuba.

Below are excerpts of Timar’s written observations during his quarter in Havana.

April 9, 2010

The most striking thing about arriving in Cuba is how little, as Americans, we know about the place. Cuba is like one of those blurred out spots on TV when they don’t want the viewers to see something. Havana is larger, more diverse as a city, and historically significant than any of us here had anticipated. The city is full of contradictions. Cubans have reason not to like Americans, but they can’t help liking them anyway because Cubans are, on the whole, lovely people.

Signs of economic hardship are everywhere, yet the old part of the city, La Haban Viejo, is undergoing restoration. Though the city dates to 1521, most of the architecture is from the Spanish Colonial period. As expected, because the Spanish came from Cadiz and Seville, there is some Moorish influence in the architecture (and actually in Cuban Spanish as well). There is a flowering of new restaurants, coffee houses, and bars catering mostly to tourists as Cuba is quite dependent on foreign currency for its economic sustenance.

There are still lots of signs that the Russians were here. It seems that Russia dumped as many of its cars that it manufactured—the Lada—on the Cubans. There are also lots of yellow buses running around that say “School Bus” on them. I think there may be a story there. There are post-1959 buildings that share the architectural charms of the Soviets.

We are almost through the first week. We’ve had a few rough patches, mainly having to do with my housing. But, it is “being worked out.” (This is no place for a Type A personality.) They have done a nice job here organizing the program for the students. By the time they go back, they should have a pretty good idea of the education system and Cuban arts and culture and history.

April 30, 2010

We have had several lectures on the education system in Cuba—both higher and lower education. Last week, we had the director of a regional medical clinic talk to our class about the relationship between the medical system and the education/preparation of medical personnel.

For obvious reasons, the education systems in the two countries—U.S. and Cuba—are very different. The philosophical foundations of education are diametrically opposed. The purpose of education here is to create patriotic, well-educated Cubans. And education does not mean literacy and math skills, but the complete development of the individual. Because of the system of government, the state provides the social, cultural capital that in the U.S. is dependent upon family and peers.

We went to an elementary school this week (K-6) and the differences between schools in the two countries could not have been more glaring. The schools are very spartan and sparse, with very small classrooms and about 15 to 20 in a classroom.

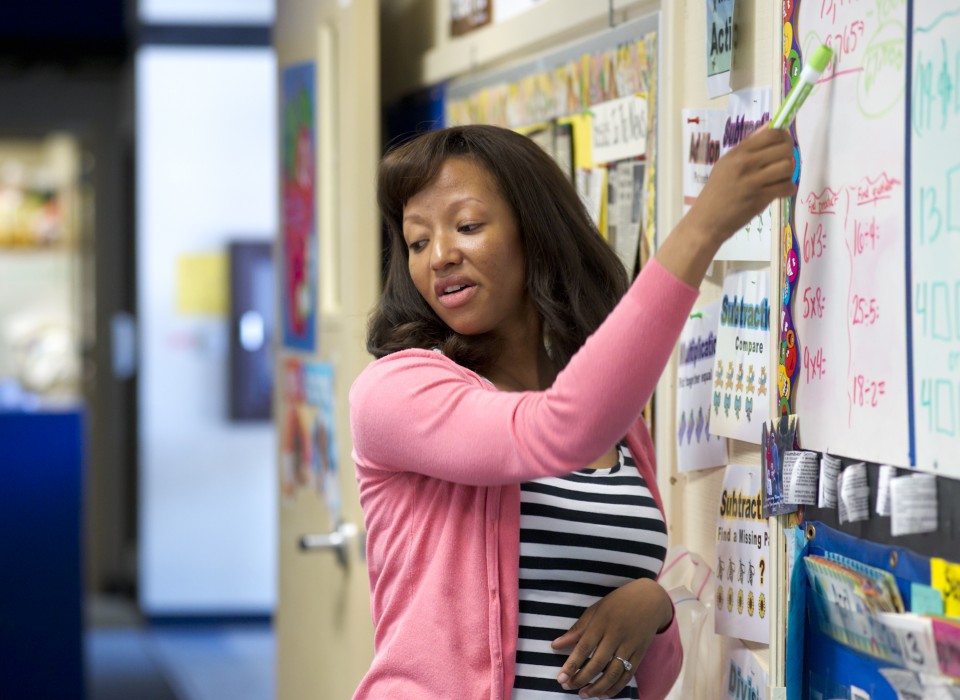

The children are very serious about school, even at an early age. The level of work that children do in the early grades is impressive. In a sixth-grade classroom, I watched part of a math lesson. The teacher was teaching students the properties of triangles—calculating angles, areas, etc. In general, students cover much more material in school than they do in the U.S. The middle school (grades 6-9) curriculum is comprised of Spanish, mathematics (including algebra, geometry, statistics, etc.), physical sciences (chemistry and physics), biological sciences, history (world and Cuban), civics, computers, physical education, arts, and English.

There is a very strong support system (supplied by the state) in the schools. That includes social/family and medical services. Teachers stay with the same group of students from grades 1 through 6. There are also mentors who are responsible for 10 students. Middle and high school teachers are trained for about 5 to 6 years. Most teachers begin their training in junior high school. The Cubans are obviously very invested in their education system and don’t leave much to chance.

Today, we went to a junior high school—grades 7 through 9—and it was really impressive. The Cubans regard those years as critical to the development—intellectual, physical, and moral/social/political—of the child and take great care in making sure that it is done right.

There is quite a bit of mentoring of new teachers and ongoing professional development for all teachers. Professional development focuses entirely on pedagogy and child development. Each child has exactly the same curriculum. It does not matter which school or which city or province. All students get the same curriculum no matter where they are. The Cubans have video lessons for each lesson and for each subject that is taught. These videos have been developed by master teachers and are available for teachers to watch. In some instances, the instruction may be on video. The idea is to create a strong professional culture among teachers and to reduce or eliminate variation among teachers in terms of subject matter and pedagogy. Teachers do not close their classroom door. In fact most classrooms don’t have doors. Teachers are evaluated on a monthly basis. Each teacher has a mentor who works with her/him.

We had students recite poetry for us, had a guitar concert, and had lots of dancing, which they get in their physical education classes. We had a student as our guide around the school—about 14 years old—who spoke perfect English. One of our Davis students was blown away by one of the Cuban students who spoke English with absolutely no accent. Finally, our students joined the middle school students in a game of volleyball. Great fun.

The students all seem to be having a great time. We had a trip planned to Varadero, one of Cuba’s nicest beaches, but it is going to rain all weekend. That’s not good news for the May Day parade on Saturday where Raul Castro is supposed to speak.

My housing is worked out. I’m getting out to ballet, concerts, lots of very good music. There is a large outdoor concert venue fairly close to where we are along the Malecon. Last Saturday night, there was a major concert there by a group that is considered Cuba’s best. Lots of people, many of them dancing the samba, including our students.

While there are all of these wonderful experiences, one can’t help but be reminded constantly of the effect that the U.S. blockade is having on Cuba. In effect, U.S. policy is aimed at starving the Cubans out. But, it hasn’t worked for over 50 years and it won’t work in the future either. The people are too resilient and resourceful.

There are lots of things here in Cuba that don’t work—the economy being one of them. But how much of that is the system and how much the embargo is hard to say.