Thriving While Black

One Researcher Seeks Answers from Those Who Have Beat the Odds

Though African Americans make up more than 7 percent of high school graduates in California, less than 3 percent graduate eligible for admission to the University of California. In fall 2014, only 500 African and African American students were admitted to a UC campus.

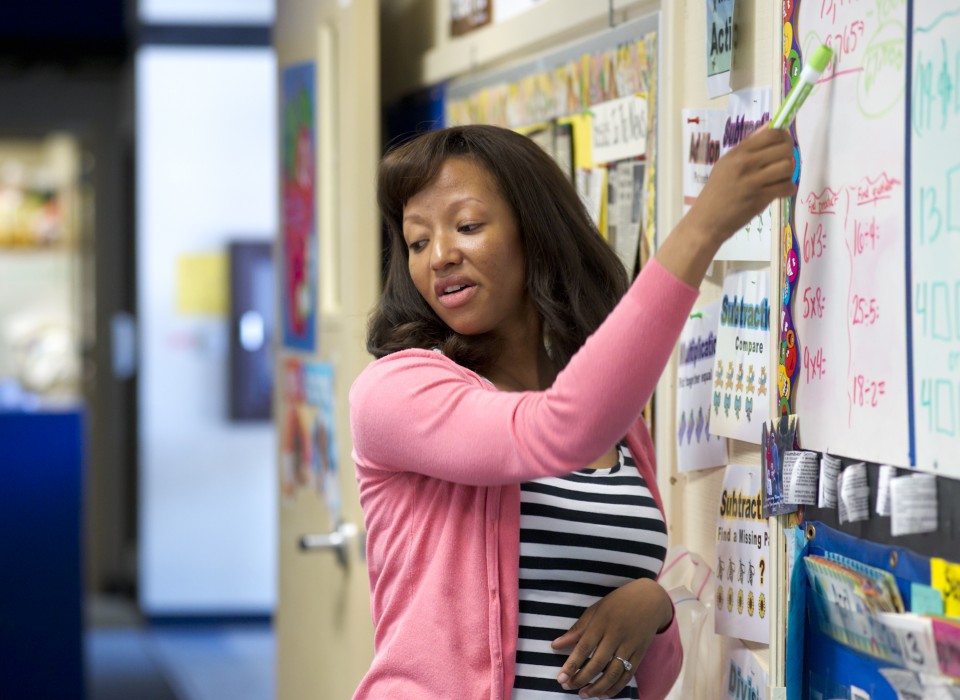

PhD student and education researcher BernNadette Best-Green wants to know why.

In a pilot qualitative study conducted through interviews of 50 African American students at UC Davis, Best-Green sought the insights of the students themselves. “Most African American young adults know what it means to combat racial discrimination associated with ‘driving while Black,’ but far too few receive K-12 educational preparation enabling them to distinguish themselves as ‘thriving while Black,’” said Best-Green.

The study sought to create a framework for understanding how K-12 schools and teachers help and hinder African American students’ college aspirations by employing critical race theory to “privilege the perspectives and lived experiences” of the high-achieving students interviewed.

Best-Green identified six characteristics that the students

perceived

to be “most helpful” and six they perceived as “most harmful.”

The most helpful teachers were considered “cultural insiders,

enablers of achievement, and mentors.” Students identified Black

teachers as “sources of inspiration and living examples of the

success that academic achievement yields,” according to

Best-Green. Teachers who set high expectations were also cited as

most helpful.

The interviews also identified schools that provided Black

students with access to extracurricular and college-prep

opportunities within a

“culture of success” as most helpful. “Rather than operating from

deficit models, these schools functioned as places where Black

students were taught to excel, even in the face of adversity,”

said Best-Green.

Not surprisingly, teachers who failed to acknowledge inequities, who “avoided empowering students” to make meaningful connections between academic content standards and their own sociopolitical realities, or who failed to provide access to rigorous coursework because of low expectations, were perceived as harmful.

One student said, “My twelfth grade AP composition teacher didn’t really prepare us that Thriving While Black: One Researcher Seeks Answers from Those Who Have Beat the Odds well for the AP exam—it was mostly just a lot of busy work! As someone who was college bound—you know—my senior year in high school, I’m thinking to myself, ‘Man, this is my senior year! Am I being challenged? How am I going to fare in college?’”

In addition to lack of access to enrichment activities and rigor, harmful schools were also cited as placing too much emphasis on collegiate athletic opportunities. “Some students were only told about college from coaches who encouraged them to pursue athletic excellence. These students also received almost no access to information about underutilized scholarships in other areas, such as agriculture,” said Best-Green.

According to Best-Green, this study lays the groundwork for a larger study to extend the research to teacher preparation and culturally relevant and sustaining pedagogy.

“Findings of the present study have important implications for

the elimination of prevalent gaps in academic achievement that

correspond disturbingly to race and social class and should be of

interest to a

diverse array of stakeholders,” said Best-Green.

Best-Green presents “‘Go Run Tell Dat!’Privileging Black Collegians’ Perspectives to Augment African American Youths’ Educational Trajectories” at the annual meeting of the American Educational Research Association on Sunday, April 19.