Case: School Garden

Elementary Classroom

Description

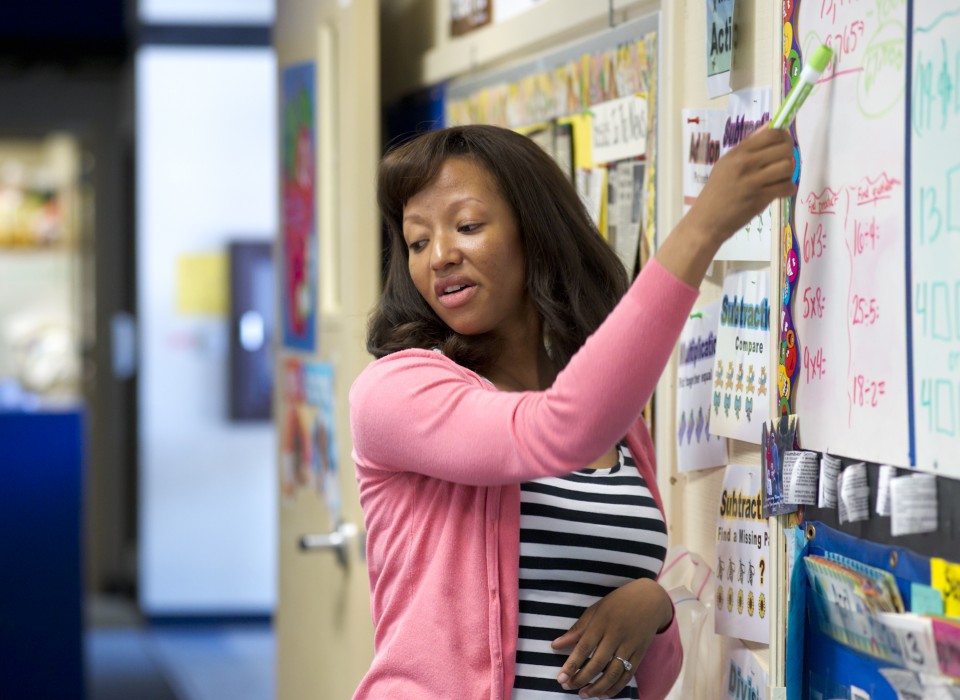

As part of an integrated science and literacy unit, 3rd grade

students participate in the Lost Ladybug

Project (LLP), a citizen science project documenting the

distribution of ladybug species across North

America. Students work in their classroom,

school garden, and science lab to (1) collect and identify the

ladybug species on their school campus in Northern California

and, (2) modify their school garden to attract more ladybugs.

Students collect and photograph ladybugs and submit the photos to

LLP, which are used to map and study shifts in ladybug

populations. In addition, students read and write about

garden and farm ecosystems,and participate in garden management

decisions related to ladybugs and pest management. Students

present their work to the community at a school-wide end of year

showcase.

Students work in their classroom,

school garden, and science lab to (1) collect and identify the

ladybug species on their school campus in Northern California

and, (2) modify their school garden to attract more ladybugs.

Students collect and photograph ladybugs and submit the photos to

LLP, which are used to map and study shifts in ladybug

populations. In addition, students read and write about

garden and farm ecosystems,and participate in garden management

decisions related to ladybugs and pest management. Students

present their work to the community at a school-wide end of year

showcase.

Species or system studied: Ladybugs.

Students document the presence of ladybug species in their school garden once a week.

Research site: School garden.

Students collect ladybugs in the garden as well as around the school campus. Students visit the garden once a week with their class.

Participants: Elementary school students.

Twenty 3rd grade students in a two-way bilingual Spanish-English immersion MAGNET school participate with their teacher, the garden teacher, and the elementary science specialist.

Structure: Classroom-based.

Students collect and submit data once a week and also engage in related reading and writing during daily literacy instruction.

Duration: 8 weeks.

The unit takes place over the course of eight weeks during the spring, when all stages of the ladybug life cycle are observable. 2016 was the first year that the teacher and school participated in the LLP.

Institution: Classroom – Elementary School.

Activities take place during the regular school day. The team of teachers incorporate LLP data collection into the integrated science and language arts unit and facilitate all learning activities. In 2016, the UC Davis research team and school administration provided teacher professional development and support for the project.

Other activities:

In addition to uploading photographs to the LLP website, students read expository text to understand ladybugs’ role in garden and farm ecosystems and each student writes a three paragraph essay about ladybugs they found. They develop posters and presentations to share their work at the end-of-year MAGNET showcase, attended by teachers, school and district administrators, parents, master gardeners and other community members. Students advise the garden teacher with recommendations about how to attract and sustain ladybug populations for integrated pest management and helped with plan implementation. Students write written reflections on their scientific work and themselves as scientists.

Curricula Resources:

- Lost ladybug project

- K-2 4-H Science Toolkit

- 3-6 4-H Science Toolkit (pdf)

- Additional unit resources – see bottom of page for photo examples

Key Practices In Action:

Through in-depth case studies of diverse YCCS projects, we have documented youth-centered key practices that are effective in promoting learning and environmental science agency. Click the headers below to learn more about what those key practices look like in this particular case.

Sharing Findings with Outside Audiences

Students shared their work with the broader community during the school’s annual MAGNET showcase presentations, which teachers, district administrators, and community stakeholders attended. The class was divided into six groups of 4-5 students and each group developed a poster and shared one component of the project. For example, one group presented the data the class gathered and submitted to LLP while another group presented the class recommendations for attracting more ladybugs to the garden. Students shared in a poster presentation format and visitors circulated fluidly to each group over the course of one hour.

Preparing and giving the showcase presentation was particularly important for students who enjoy science but are reluctant to assert themselves or less confident in their abilities. For example, Julia was able to position herself as an expert to both her peers and community members, although she was generally quiet during group discussions and two boys in the group did most of the talking. As the students prepared their presentations, the teacher played a key role by suggesting that Julia use the iPad during the presentation. This enabled Julia to take the lead during the showcase, showing visitors how the group collected and submitted their LLP photographs.

Some students had additional opportunities to share their work during the eight-week unit before the showcase. Two groups presented their posters to visiting educators from Australia and three students led members of a parent club to the garden where they demonstrated how to photograph a ladybug and upload the picture to LLP. One girl, Kira, felt especially proud of leading the parent garden tour. She shared that adults typically “don’t pay attention to students” but when she was in the role of school garden expert, they not only paid attention to her, but she was also able to teach adults what she had learned.

Ensuring High Data Quality

While some CCS projects design multiple ways for students to take ownership of collecting high quality data, LLP scientists review every photo and identify the ladybug species to ensure their data quality standards. This seemed to limit types of student ownership of data quality.

However, we observed more subtle evidence of ownership when students submitted data to the national contributory CCS project. First, students were in charge of taking good photographs. The teacher initially modeled scientific photography by showing students how to freeze a ladybug for 5 minutes so it wouldn’t move, take the photo on a piece of white paper, and ensure the ladybug was large and in focus. Students discussed whether or not the quality of the photograph was good, mentioning characteristics like whether or not the ladybug was in focus. They occasionally asked the teacher to refreeze the ladybugs when they were moving or retook photographs. In this way, students took responsibility for submitting data to scientists that they thought were high quality.

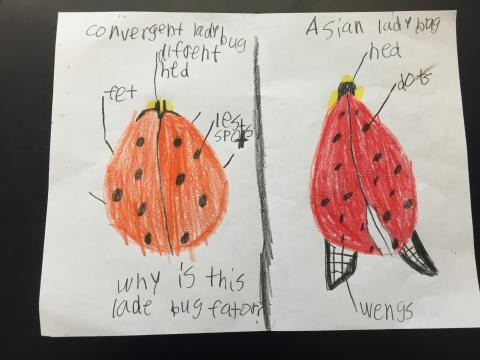

In addition, students determined which ladybugs they should photograph and submit to LLP. The educator taught students how to make a scientific sketch, rich with detailed observations and labels. This helped students make close observations and learn to accurately identify different ladybug species, including the most common ladybug in their garden, the convergent ladybug (Hippodamia convergens). As LLP is interested in species distribution rather than abundance, students discussed whether or not they should upload multiple photographs of the same species. After the first two days of data collection, students decided to only upload photographs of new species they observed.

Interacting with Complex Social Ecological Systems

Students learned about the ecological relationships in the garden as well as human management of the garden for food production through their integrated experiences in the garden and classroom. As they collected LLP data in the garden, students observed how the large aphid population was damaging their crops and how ladybugs acted as a natural predator. Students also read articles about ladybug life histories and attracting ladybugs to the garden during their language arts lessons. The teacher then asked students to generate multiple solutions for how to control the aphid population in the garden. Students shared their ideas, engaged in respectful argumentation, and decided as a group on a management strategy that involved cutting down annual food crops infested with aphids and planting perennial native plants to provide year round ladybug habitat.

The garden teacher helped students carry out part of their plan, cutting down annuals and continuing monitoring. Through this integrated unit, students experienced themselves as actors in a garden ecosystem and came to understand how humans influence and are influenced by ecological processes. This understanding extended for weeks after the unit had ended, as students continued bringing ladybugs they found from home to the garden to help control the aphid population.

YCCS Products

Data: Weekly photographs of ladybugs

- Why: Documenting the distribution of ladybugs across North America helps scientists assess how and why species composition is changing and the impact it will have on ecosystems.

- Audience: Entomologists at Cornell lab of ornithology. When students upload photographs, entomologists identify the species and add the photographs to the project database.

- Audience: The general public is able to access all of the LLP data through the LLP website

- Impact: Students documented 5 species of ladybugs which were added to the broader LLP database.

Posters: Posters that were used at MAGNET showcase and open house to communicate the work students had done to their local community

- Why: Because the school is a MAGNET school, they have an annual showcase to share with the broader community what is happening at the school. The citizen science work was central to the ladybug unit and 3 of the 6 groups shared about what they had done with citizen science.

- Audience: Teachers, district administrators, parents, community stakeholders, other MAGNET schools

- Impact: Though many community members were already knowledgeable about agriculture and ecology, the showcase introduce information about ladybugs and integrated pest management to many community members.

Outcomes & Evaluations

The teacher and school had four main outcomes for the students in language arts, science, and citizenship. First, students used their science work as material for writing an. Student essays were scored by two teachers using a rubric and students were expected to demonstrate a writing level of three out of four. These essays were used immediately to assess students writing level and the school-wide writing goals. The school also saved them as part of student writing portfolios for future teachers’ use and the school’s annual MAGNET program evaluation.

Second, students were expected to communicate through oral presentation, which was informally assessed during showcase presentations.

Third, the teacher assessed student engagement in the scientific practice of argument through evidence, a practice emphasized in the Next Generation Science Standards. This was assessed informally through the students use of evidence from their observations and reading.

Finally, the principal hoped that student participation in citizen science could address two of the school’s six character goals: collaboration and citizenship. The teacher assessed these two goals and they were incorporated into student scores on their district report card.