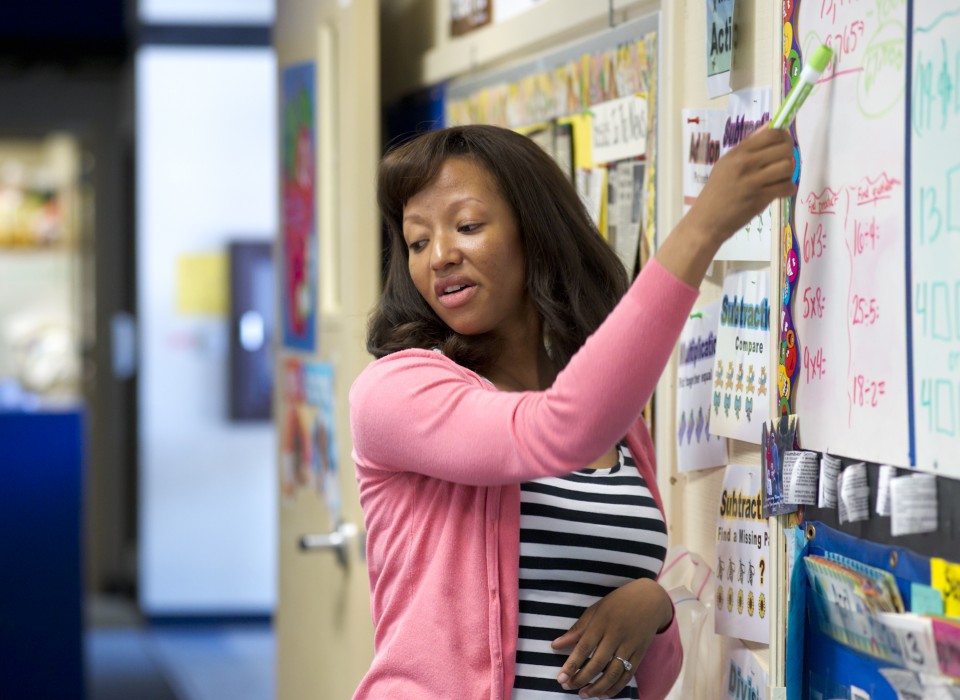

Claudia Rodriguez-Mojica Joins School of Education Faculty

This summer, the School of Education

welcomed new faculty member Claudia

Rodriguez-Mojica as an Associate Professor of Teaching in

Education and the Spanish Bilingual Authorization Coordinator.

She comes to UC Davis after eight years as an associate professor

of teacher education at Santa Clara University, and a previous

role as a Senior Researcher at nonprofit Education Northwest in

Portland, Ore.

This summer, the School of Education

welcomed new faculty member Claudia

Rodriguez-Mojica as an Associate Professor of Teaching in

Education and the Spanish Bilingual Authorization Coordinator.

She comes to UC Davis after eight years as an associate professor

of teacher education at Santa Clara University, and a previous

role as a Senior Researcher at nonprofit Education Northwest in

Portland, Ore.

Rodriguez-Mojica is the principal investigator and project director on a $2.6 million grant from the U.S. Department of Education’s Office of English Language Acquisition to support Spanish–English bilingual instruction in California and New Mexico, including the development and implementation of workshops in Spanish for bilingual teachers to gain and refine the skills they need to teach in K-8 dual language classrooms.

Rodriguez-Mojica has been away from the region where she grew up for over a decade and is glad to be back. “Being in Davis again really feels like coming home for me,” she said. “I’ve spent so many formative years in Northern California. And now I’m supervising credential candidates at Beamer Elementary in Woodland where I was a student teacher myself. My former resident teacher and mentor is still at Beamer. I learned so much about being a learner and a teacher in this geographic space that this really feels like it’s the place I’m meant to be.”

A child of immigrants from Michoacan, Mexico, Rodriguez-Mojica grew up in the very small town of Hamilton City in Northern California, speaking only Spanish until she started school. “My siblings and I benefited from a lot of programs for families like ours that were classified as English learners,” she said. “We were in migrant education, my sister and I participated in Educational Talent Search, and my brothers were in Upward Bound.”

While earning her bachelor’s degree in human development and minor in Chicana/o studies at UC Davis, Rodriguez-Mojica joined the California Mini-Corps, a TRIO program connected to migrant education. She was placed at an elementary school in Winters and served as a tutor for migrant education students.

“I worked in a social studies class with a lot of students who were native Spanish speakers who were at the early stages of acquiring English,” she said. “I translated what the teacher was saying, sometimes teaching the exact same content in Spanish so they could access it. Through that I found my love for teaching. As a child playing with my cousins I was always the teacher, but somehow it had never clicked for me before that I could be a teacher myself.”

After graduation from UC Davis,

Rodriguez-Mojica earned her multiple subject teaching credential

with a bilingual authorization (formerly known as BCLAD) at

Sacramento State, and then was a bilingual dual-language Spanish

and English classroom teacher for first and third grade classes

in Winters and East San Jose. Her experience of teaching in a

school district that required a quick transition from instruction

in Spanish to instruction in English prompted her return to

graduate school.

After graduation from UC Davis,

Rodriguez-Mojica earned her multiple subject teaching credential

with a bilingual authorization (formerly known as BCLAD) at

Sacramento State, and then was a bilingual dual-language Spanish

and English classroom teacher for first and third grade classes

in Winters and East San Jose. Her experience of teaching in a

school district that required a quick transition from instruction

in Spanish to instruction in English prompted her return to

graduate school.

“I was struggling to help my third-grade students and kept thinking that there had to be a better way to do this,” she said. “That sparked my interest in going back to grad school, where I could have the time and space to learn what the research said, and then come back to my classroom to implement what I’d learned.”

Rodriguez-Mojica went to Stanford University to earn a master’s degree in linguistics, and quickly learned that there was not yet clear research on how to best serve her students as they transitioned to English-only instruction. She decided to pivot and become a researcher herself, feeling that her background as an English learner would give her a unique lens through which to engage in that work. She stayed at Stanford to earn a PhD in curriculum studies and teacher education.

Rodriguez-Mojica’s doctoral research focused on assessing the English skills of students who were classified as English learners, and how close those skills were to meeting state of California academic and English language proficiency standards. For months, she audio-recorded fourth-grade students who were native Spanish speakers while they participated in class.

“The students would go about their day wearing little audio recorders clipped to their clothes or in their pockets,” she said. “At the beginning it was a little challenging—they would kind of talk into their recorder, or be really quiet. But as the weeks went on they completely forgot they even had them, and sometimes I had to remind them to take off their recorder when they were leaving the classroom.”

Rodriguez-Mojica determined that English learners were able to access academic content and engage in critical language practices in ways that were missed by formal assessments. “Having all that data collected in real time shined a light on how test scores are helpful in some ways but are not the only way we need to assess these students,” she said. “There is so much more we can observe if we listen to what students are actually saying and doing when they’re learning in the classroom.”

Rodriguez-Mojica also began investigating whether classroom practices and techniques used with English learners are of demonstrable benefit. “I think we just make the assumption that of course something is helping because we mean for it to help,” she said, “but sometimes it doesn’t.”

On a large scale, Rodriguez-Mojica cited the example of policies that separate English learners from native speakers of English, which inadvertently removes the opportunity for students to learn language skills from their peers, and may also result in less-rigorous standards. At the level of one-on-one interactions, she noted that when teachers habitually correct the grammar or vocabulary used by English learners, important information may be lost.

“What we don’t realize is that while we’re focusing on the way that they’re structuring their sentences we’re not really listening to the message they are communicating,” she said. “The student may have given an amazing summary of what they just read or made a wonderful prediction. Those responses are tied to the standards, and the students are meeting them, but that can be overlooked when the teacher focuses more on the words and structure even when it’s not English language development time.”

Rodriguez-Mojica encourages her teaching credential candidates to look for what they might be missing while they’re teaching. “I tell them to ask themselves what real-time evidence they have about whether a practice is actually helping their students,” she said. “I want to bring my research back to practice so that teachers will learn to analyze what they’re doing and whether something is working.”