Using Environmental Literacy as the Through Line, All Standards All Students: A Focus on Equity and Access

This article was originally published on November 17, 2020 on Ten Strands. To view the original post, click here.

“Research shows that weaving together science and language development can increase students’ academic performance in reading, writing, and science simultaneously.”

~ Sarah Feldman and Verónica Flores Malagon, “Unlocking Learning: Science as a Lever for English Learner Equity”

The path that led me to environmental literacy education was less than direct, more of a meandering road. Having spent the early part of my teaching career in the primary grades, in 2003, the same year that California’s Education and the Environment Initiative (EEI) was passed, I began to engage in action research that looked into best practices for teaching foundational literacy. The more I dug into the research, and looked at data from my own classes, the more it became clear that for many students the most effective way to deepen literacy engagement and skill building was through authentic engagement in content areas, specifically science.

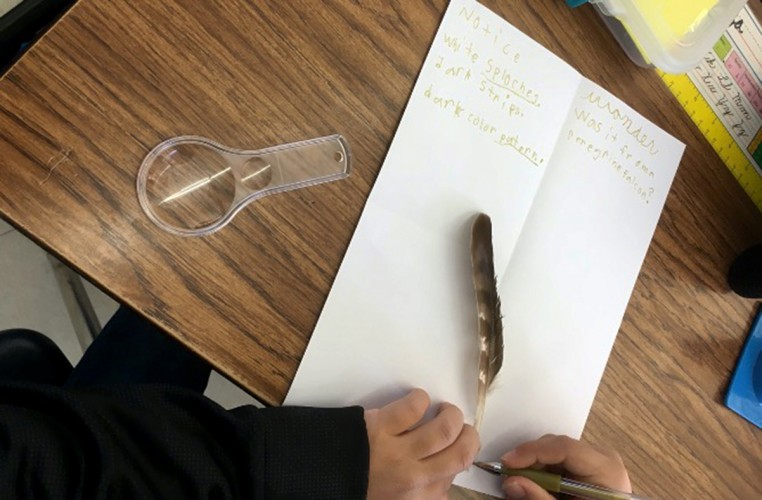

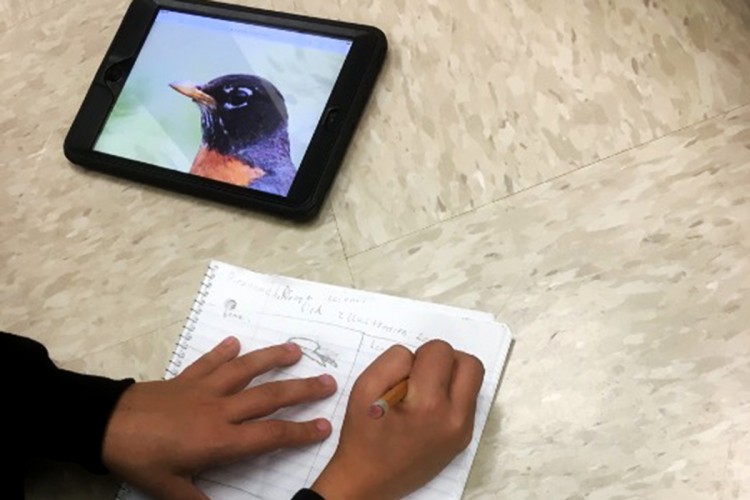

When science instruction was placed at the forefront of lessons, instead of relegated to the occasional “enrichment activity” as was so often the case in elementary schools, I found that both language and reading skills outpaced expected growth. Students, especially English language learners, saw that there was a purpose to their reading, writing, and speaking. As they began to express their understanding of novel phenomena, all students had common experiences to highlight a need for deepening understanding of new vocabulary. Science, for me, became a means to focus on equity and access within my classroom and to highlight the need for all students to have access to a comprehensive, content-rich program. For the next 10 years, I focused my efforts on bringing science content to the forefront of literacy lessons. By doing so, not only did all students gain access to rich content instruction, they also gained skills in deepening scientific discourse, reading, and writing. I focused on engaging all learners in discussions steeped in scientific observations, and used student exploration to ensure accessibility to the content.

When science instruction was placed at the forefront of lessons, instead of relegated to the occasional “enrichment activity” as was so often the case in elementary schools, I found that both language and reading skills outpaced expected growth. Students, especially English language learners, saw that there was a purpose to their reading, writing, and speaking. As they began to express their understanding of novel phenomena, all students had common experiences to highlight a need for deepening understanding of new vocabulary. Science, for me, became a means to focus on equity and access within my classroom and to highlight the need for all students to have access to a comprehensive, content-rich program. For the next 10 years, I focused my efforts on bringing science content to the forefront of literacy lessons. By doing so, not only did all students gain access to rich content instruction, they also gained skills in deepening scientific discourse, reading, and writing. I focused on engaging all learners in discussions steeped in scientific observations, and used student exploration to ensure accessibility to the content.

In 2013, when California adopted the Next Generation Science Standards (NGSS), I joined a team at the UC Davis School of Education: the Innovations in STEM Teaching and Research project, or ISTAR. ISTAR researches best practices in engaging students in the three dimensions of NGSS, with a special focus on the scientific practices. As we looked at engaging K–12 students in all three dimensions of NGSS, it became clear that for students to have access to the content and courses in middle and high school, educators needed to build a foundation for scientific literacy in elementary school. To me, as a reading teacher steeped in the developmental approaches to literacy acquisition and instruction, this made perfect sense. We as educators could not continue to look at science as a content area that could be taught like a puzzle, adding one piece at a time and hoping students would be able to put the pieces together. Rather, we needed to view it more as a scaffold, helping students build skills one upon another to create a strong foundation of inquiry based on observations, reading, writing, and speaking.

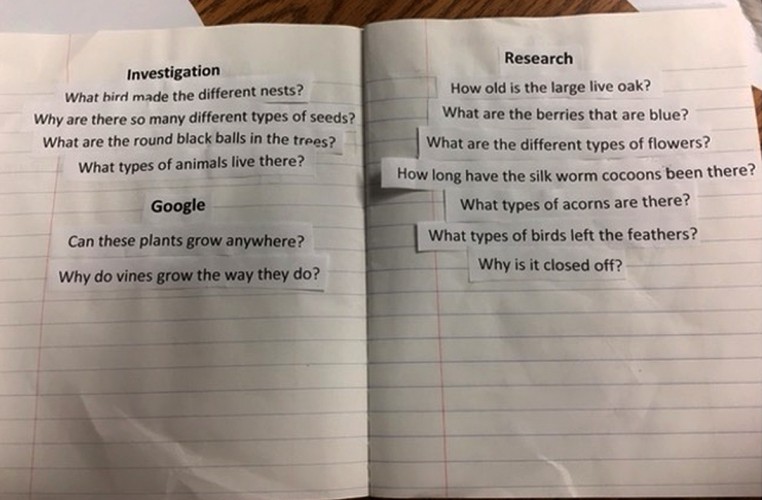

It was during this time of research, looking into best practices and making the shift to NGSS, that I was introduced to citizen science by a member of the ISTAR team, Heidi Ballard, professor of environmental science education at UC Davis and founder and faculty director of UC Davis School of Education’s Center for Community and Citizen Science. One of Heidi’s areas of research is youth-focused citizen and community science (YCCS). Until then, I had never heard the terms community science and citizen science. As I learned more about it, I recognized it as a potential through line, connecting content-area instruction to place-based, environmentally focused inquiry that engaged students in not only the three dimensions of NGSS, but also the authentic application of common core ELA and math skills. The key word there was authentic. YCCS allowed for authentic engagement with both the content standards and the Environmental Principles and Concepts (EP&Cs) as I focused on supporting students in developing environmental science agency.

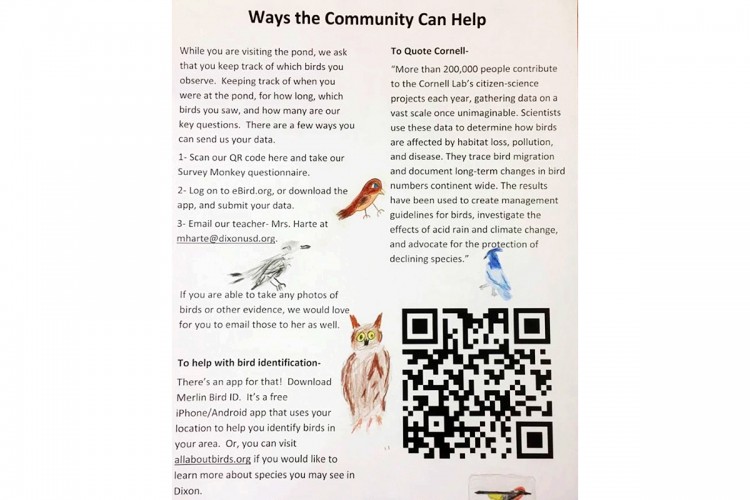

The EP&Cs had been developed before the adoption of the NGSS, but it was during this same time that I began to engage with the EP&Cs in my classroom directly and, through YCCS, authentically. By connecting students directly to content-area instruction through authentic inquiry and research, students began to not only deepen their understanding of the EP&Cs, but also to develop environmental science agency as they gained expertise and reflected on the results of their research. Students collaborated with their local community, advocated for change at the city and campus levels, reached out to the scientific community, and began to identify as experts in their field as they deepened their understanding of the systems in which they lived, learned, and played. Their engagement and advocacy was proof of how impactful this shift in approach that focused on inquiry-based environmental literacy was for student learning.

This year, in addition to my role as the education project manager at the Center for Community and Citizen Science, where I support educators and parents in engaging students with YCCS, I have also begun work as the program manager of environmental literacy and instruction at the Solano County Office of Education. This is a new and very exciting opportunity to build out an environmental literacy program within the county, built on current environmental literacy research and pedagogy, that supports classroom teachers as well as informal educators and parents. In this new role, I have had the opportunity to work with administrators, teachers, and expanded-learning program educators, including outdoor education providers, educators who manage on-campus before- and after-school programs, and those who wish to support environmental literacy instruction within the county. Through this collaborative effort between the county and UC Davis, I am building out a robust network of resources for parents, students, and educators of all types as we work with students who engage with and understand the interconnected nature of the world around them.