New Teachers Learning Disciplined Improvisation for Meaningful

Talk in Diverse Classrooms

Conceptions of Discussion, Teaching, Teacher Learning

We clarify conceptions. By discussion, we mean group

structures for recall, language production/elaboration, exploring

interpretations, linking content and community, and working

through problems and conflicting ideas. Teaching through

discussion includes substantive engagement associated with

academic learning, using authentic questions, uptake for cohesive

discourse, and high-quality feedback (Applebee, Langer, Nystrand,

& Gamoran, 2003; Nystrand, 1997). Such discussion facilitates

discovery and display through language (Bunch, 2013); scaffolding

language of schooling (Schleppegrell, 2004); and leveraging

linguistic resources in students’ communicative repertoires

(Martinez, Morales, & Aldana, 2017). Such teaching includes

disciplined improvisation with moments co-constructed in

real time. By disciplined we refer to content purposes

for discussion, repertoires of knowledge and techniques

(Erickson, 2011), repertoires of practice (Gutierrez & Rogoff,

2003), structures and constraints (Hammerness et al., 2005;

Sawyer, 2004). By improvisation we mean in-the-moment

decision-making and microadaptations (Barker, 2012; Corno, 2008)

to focus engagement and learning.

Relatively little is known about how teachers learn to

enact discussion: conceptual and practical tools needed

(Williamson, 2013), adaptations teachers learn to make, a

typology of moves available. A slim literature finds

microadaptations in literacy lessons include: modifying

objectives, changing means by which objectives are met (adapt

routines, strategies, materials, actions), inventing examples or

analogies, inserting mini-lessons, suggesting different ways

students can handle a problem, and resequencing or omitting

activities (Duffy et al., 2008; Parsons, 2012). Adaptations

require keen perception, and issues warranting adaptation may go

unnoticed, especially by novices who may not see “telltale signs

for adjustment” (Duffy et al., 2009, p. 168). Pattern recognition

requires development, as it is seldom a natural process for

teachers (Korthagen, 2010). Challenges of facilitating oral

language activity intensify for many new teachers underprepared

to support learners in linguistically complex classrooms (Ball,

2009; Darling-Hammond, 2006; Gándara, Maxwell-Jolly, & Driscoll,

2005), such as those we feature in our project.

As classroom talk may be fast-paced and ephemeral (Wortham,

2008), adaptation in-the-moment is demanding. Teacher development

that supports perceptual skills in noticing language

contributions, nonverbal cues, and efforts at discourse, and

metacognitive processing of action and talk may support

teachers’ capacity to reflect-in-action (Schon, 1983; Yanow &

Tsoukas, 2009) and make informed choices that support learning.

We need to know much more about adaptations a teacher might make

and ways teachers learn to enact them.

Cognition and Teacher Learning for Discussion

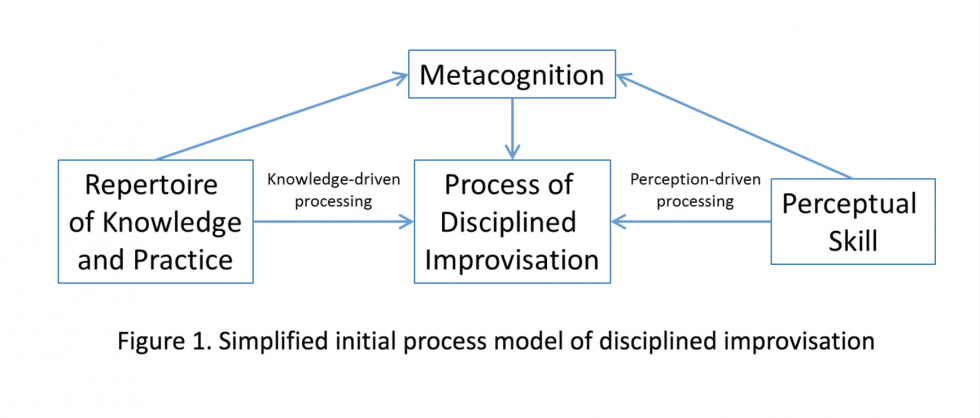

Our project investigates cognitive underpinnings of disciplined

improvisation, a form of adaptive expertise (Bransford et al.,

2005) that benefits from conceptually rich knowledge of teaching

practices and their effects. Like other expert decision-making,

disciplined improvisation involves knowledge-driven and

perceptual-driven processes (also called top-down and bottom-up

processing; Chi, Feltovich, & Glaser, 1981). For example,

teachers must foster discourse incorporating all voices (e.g.,

noticing potentially relevant observations voiced outside of

“standard” academic language). A number of studies explore

teacher noticing (Sherin, Jacobs, & Phillip, 2011), but

perceptual aspects of disciplined improvisation have received

little attention.

Instruction focused exclusively on building repertoires of

knowledge typically fails to influence practice (Bransford et

al., 2005). This problem of enactment arises from a

paucity of opportunity to rehearse these learned strategies. Lack

of focus on perceptual processing likely exacerbates the problem,

as teachers may fail to notice conditions of applicability. We

will develop both a process model (how does disciplinary

improvisation work in-the-moment) and a learning model

(how do teachers learn to enact disciplined improvisation) to

support classroom discourse in linguistically diverse classrooms.

There remains little empirical elaboration of underlying

processes of disciplined improvisation. Sawyer (2011) argues that

teaching expertise is “mastery of a corpus of

knowledge—ready-made, known solutions to standard problems–but

in a special way that supports improvisational practice.” In our

simplified process model (Figure 1), disciplined improvisation is

informed by knowledge and practice, informed by

perceptual learning of meaningful patterns, and

ultimately responsive in-the-moment—through

microadaptations—to diverse students’ learning, language, and

lives. Metacognition—awareness of one’s own knowledge and skill,

and ability to control one’s cognition—knits these pieces

together. Our research will elucidate repertoires of knowledge

and practice and perceptual skills—and relationships between

them—necessary to support discourse in linguistically diverse

classrooms.

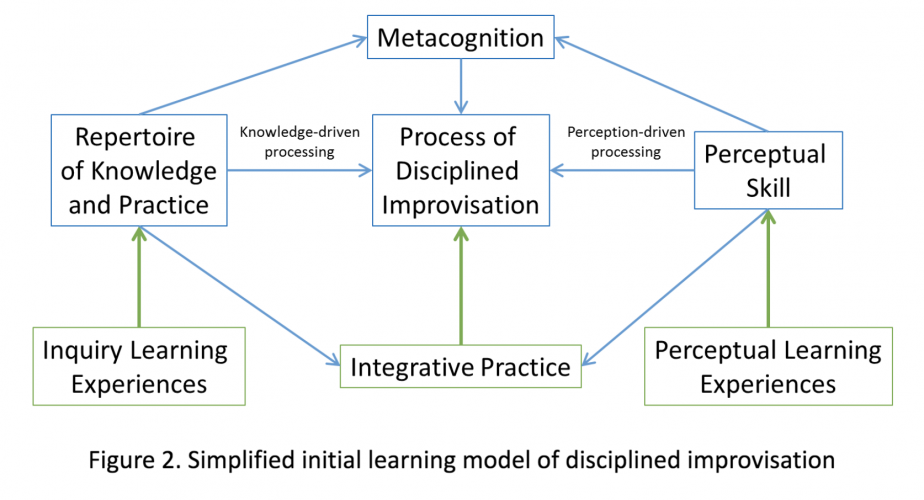

Our initial model of how disciplined improvisation can be learned

(Figure 2) is also highly simplified: teachers need to develop

their repertoires of knowledge and

practice, they need to develop

perceptual skills, and they need ample

opportunities to develop the metacognitive

skills needed to integrate knowledge-driven and

perception-driven processing in authentic contexts. Our

definition of teacher learning is growth in any of these

three areas. With teacher partners, we will design

educational experiences for early-career teachers so we can

observe, analyze, and improve designs for teacher learning across

these three areas.

Refined Research Questions

Our overarching question is:

How do teachers learn to enact disciplined improvisation

in support of discourse in linguistically diverse

classrooms?

We examine this overarching question through three main

sub-questions. For each, we look at the nature of the expertise

(process model) and how it is learned through experience

(learning model):

RQ1. Learning the dialogic toolkit

- What knowledge and practices support

disciplined improvisation in linguistically diverse classrooms?

- What learning activities and tools support their development?

RQ2. Learning to see in discourse

- What perceptual/noticing skills support

disciplined improvisation in linguistically diverse classrooms?

- What learning activities and tools support their development?

RQ3. Enacting disciplined improvisation in the moment

- What metacognitive skills support the

integration of knowledge, practice, and perception into

disciplined improvisation?

- What learning activities and tools support their development?

Alignment with Program Goals and Response to Feedback

Early-career teacher learning. We have found

even when preservice teachers (PSTs) develop rich repertoires of

knowledge and practice for discussion through coursework, first

enactments are fraught with complexity, needing greater retrieval

of coursework information and knowledge synthesis. TE needs

innovative pedagogical models to develop agentive educators and

engage teachers in research-informed practice, particularly in

light of “reforms” stripping TE of its research-based and

visionary roles (Zeichner, 2014). As part of a McDonnell-funded

collective, we will add focus to preservice/early-career teachers

and models of their learning and of TE pedagogy to support

development of novices for communicative work in diverse

classrooms.

ELA, then science. Responding to feedback, we

examined ways our design-based research with TE and teacher

partners has yielded rich extant databases in ELA that inform

study plans. Emergent findings will inform focus on elementary

science, so we can test our models, aligned with the program call

for “cross-cutting impact across subject areas and ages.”

Scale-down. We focus now on nuanced examination

of teacher learning and model development in California’s richly

diverse population, eliminating the UMD bilingual teachers team.

We also no longer will study dissemination with CSU, instead

tapping CSU faculty as advisors and going deep with preservice

and early-career teachers in local schools.

Virtual reality (VR). Feedback raised VR

concerns: transferability, “authenticity” versus live

improvisation, cost/sustainability. We recognize concerns but

find VR a promising, rapidly-evolving avenue with affordances

that can be leveraged, combined with face-to-face teacher

learning supports (teacher educator feedback, professional

learning communities). Opportunity for iterative change over time

in a lower-risk environment (real students not impacted as

teachers practice) is a significant VR affordance, as is creation

of tailored, reusable learning environments ensuring PSTs sustain

practice with important discussion aspects to which they may have

uneven exposure in real-world settings (e.g., facilitating

discussion in linguistically diverse classrooms, distinguishing

uptake/pseudo-uptake).

Another key VR affordance is ability to record authentic

interactions to return to and iterate upon, making ephemeral

discussion a durable artifact for analysis and improvement. When

people interact with human-controlled avatars versus

algorithm-controlled agents, their physiological reactions and

behaviors are similar to how they would react to real people

(e.g., Donath, 2007; Hoyt, Blascovich, & Swinth, 2003; Okita,

Bailenson, & Schwartz, 2008). This suggests that immersive

virtual environments with avatars that we would use may provide

novel, contextualized classroom talk situations that are

realistic, potentially augmenting face-to-face preparation by

repeatedly drawing teachers’ attention to consequential elements

of classroom discussion that can go unseen or unexplored in

real-world settings.

We are aware that VR study reviews reveal uneven results (e.g.,

Khan et al., 2009; Laver et al., 2015), and there is need for

rigorous research that explicitly addresses transfer from virtual

to real-world settings. However, we are encouraged by some

investigations suggesting cognitive strategy elements of these

two environments are broadly equivalent and that there is a clear

positive transfer effect from virtual to real training when

virtual task elements closely approximate real-world task

elements (e.g., Rose et al., 1998, 2000). We will cautiously

build on this promising research by learning about teachers’

local contexts and histories in classroom discussion practices,

then designing virtual environments that reflect realities of

those contexts. Additionally, our approach to transfer differs

from many reviewed studies (particularly in rehabilitation) which

feature spontaneous transfer. We will support teachers in guided

transfer through activities designed to bridge learning between

virtual and real-classroom environments. Finally, we intend to

contribute to literature on VR for training with systematic

reporting of study details and investment in understanding

teachers’ learning and development across virtual and

face-to-face settings over time.