Project Update: Supporting Community and Citizen Science at the Elwha ScienceScape Symposium

The removal of two large dams from the Elwha river in the ancestral lands of the Coast Salish peoples was the first large-scale dam removal of its kind in the world. This effort has inspired many other watershed-scale restoration projects and dam removal organizations both nationally and internationally. CCS has an important role to play in the Elwha: the Lower Elwha Klallam Tribe (LEKT) and other local communities were a large part of the original drive to remove the dams, and as funding and policy requirements sunset, ongoing monitoring will need to be increasingly taken up by stewards beyond federal and state agencies. For us at the Center for Community and Citizen Science, this place and moment offer a remarkable opportunity to help center participation in the ongoing stewardship of a world-renowned watershed-scale restoration project. How can we support and elicit ideas for public involvement in understanding the Elwha’s continuing transformation?

To mark the ten-year anniversary of

the removal of the dams, the Elwha scientific community came

together to coordinate sampling efforts, plan for future

long-term monitoring, and synthesize data collected to date – an

effort called “Elwha ScienceScape.” Supported by the Resources

Legacy Fund (RLF), the ScienceScape effort built on their

April workshop by holding a public event at Peninsula College

and a science symposium at the NatureBridge Olympic Campus in

late summer of 2022. We joined ScienceScape for these events to

learn about the Elwha River’s first 10 dam-free years and to

celebrate the successes of these groundbreaking restoration

projects, while also recognizing ongoing downsides and areas

for growth. We were also able to join agency and tribal

scientists and community groups to observe (and participate in!)

emerging participatory science projects. We had been discussing

the past, present, and future of CCS on the Elwha with scientists

and community organizations over the preceding four months, and

we were excited to get a chance to experience the place in

person, meet our collaborators face-to-face, and continue those

conversations.

To mark the ten-year anniversary of

the removal of the dams, the Elwha scientific community came

together to coordinate sampling efforts, plan for future

long-term monitoring, and synthesize data collected to date – an

effort called “Elwha ScienceScape.” Supported by the Resources

Legacy Fund (RLF), the ScienceScape effort built on their

April workshop by holding a public event at Peninsula College

and a science symposium at the NatureBridge Olympic Campus in

late summer of 2022. We joined ScienceScape for these events to

learn about the Elwha River’s first 10 dam-free years and to

celebrate the successes of these groundbreaking restoration

projects, while also recognizing ongoing downsides and areas

for growth. We were also able to join agency and tribal

scientists and community groups to observe (and participate in!)

emerging participatory science projects. We had been discussing

the past, present, and future of CCS on the Elwha with scientists

and community organizations over the preceding four months, and

we were excited to get a chance to experience the place in

person, meet our collaborators face-to-face, and continue those

conversations.

Joining current CCS field sampling projects

Our trip included accompanying researchers and community partners as they jointly discussed taking up new forms of public participation in environmental monitoring.

NOAA Scientists Sarah Morley and Aimee Fullerton work with Joel Green of Clallam County Streamkeepers and Ryan Meyer of the UC Davis Center for Community and Citizen Science to install new temperature loggers which can be downloaded with a smartphone.

For example, NOAA maintains a

network of water temperature loggers throughout the watershed,

providing crucial data used by scientists at the Lower Elwha

Klallam Tribe, NOAA, USGS, Olympic National Park, and other

organizations. A variety of local groups may be able to step in

and help with crucial tasks such as periodic data downloads and

monitoring the condition and positioning of each sensor in the

network. On this trip, Joel Green, who leads the Clallam County

Streamkeepers, explored ways of bringing Streamkeeper volunteers

into the collective effort to sustain the temperature monitoring

network, focusing on the front country loggers that are more

easily accessible by car. Streamkeeper volunteers already track a

variety of water quality measurements in the local area, but

managing temperature loggers in the Elwha would be a new activity

for them.

For example, NOAA maintains a

network of water temperature loggers throughout the watershed,

providing crucial data used by scientists at the Lower Elwha

Klallam Tribe, NOAA, USGS, Olympic National Park, and other

organizations. A variety of local groups may be able to step in

and help with crucial tasks such as periodic data downloads and

monitoring the condition and positioning of each sensor in the

network. On this trip, Joel Green, who leads the Clallam County

Streamkeepers, explored ways of bringing Streamkeeper volunteers

into the collective effort to sustain the temperature monitoring

network, focusing on the front country loggers that are more

easily accessible by car. Streamkeeper volunteers already track a

variety of water quality measurements in the local area, but

managing temperature loggers in the Elwha would be a new activity

for them.

We accompanied NatureBridge staff members to meet with Sarah Morley from NOAA at the mouth of the Elwha to develop a stable isotope sampling activity for students. This contribution would provide valuable data for understanding how the aquatic food web is changing over time as salmon populations continue to rebuild following dam removal. Stable isotopes are used to track the origin of nutrients that pass through the system. If these nutrients are coming from the ocean, the implication is that salmon are bringing those nutrients up into the river system and benefiting the food web in ways that had been prevented by the dams for more than a century.

We also joined USGS and Lower Elwha

Klallam Tribe researchers as they deployed small mammal traps on

one of the former reservoirs – continuing the study of how the

river’s food web is changing as the landscape and vegetation

continues to evolve since dam removal. This project often

involves volunteers, but is not specifically designed as a

citizen science project. Researchers noted that the relative

tradeoff between the effort to bring volunteers along and the

benefit the volunteers bring can vary over time, but noted that

there have been times where the extra help was absolutely

critical.

We also joined USGS and Lower Elwha

Klallam Tribe researchers as they deployed small mammal traps on

one of the former reservoirs – continuing the study of how the

river’s food web is changing as the landscape and vegetation

continues to evolve since dam removal. This project often

involves volunteers, but is not specifically designed as a

citizen science project. Researchers noted that the relative

tradeoff between the effort to bring volunteers along and the

benefit the volunteers bring can vary over time, but noted that

there have been times where the extra help was absolutely

critical.

Elwha ScienceScape Public Event and Scientific Symposium

The public event – with well over

200 attendees! – featured speakers summarizing the state of the

Elwha system 10 years after dam removal, giving a report on the

current status of the upcoming Klamath River dam removals (slated

to begin in 2023), on Dam Removal Europe and the work being done

abroad, and on RLF’s regional work supporting dam removals in the

American West. Following these presentations, the Peninsula

College

Longhouse ʔaʔkʷustəŋáw̕txʷ House of Learning graciously

hosted a poster session.

The public event – with well over

200 attendees! – featured speakers summarizing the state of the

Elwha system 10 years after dam removal, giving a report on the

current status of the upcoming Klamath River dam removals (slated

to begin in 2023), on Dam Removal Europe and the work being done

abroad, and on RLF’s regional work supporting dam removals in the

American West. Following these presentations, the Peninsula

College

Longhouse ʔaʔkʷustəŋáw̕txʷ House of Learning graciously

hosted a poster session.

The Longhouse is the first of its kind, representing a

partnership between Tribes and the Community College, and we were

grateful for their hosting and the presence and performance of

the Lower Elwha Klallam Tribe  drummers and singers who gave a welcome at both the

presentations and the poster session. Poster presenters shared

research on a variety of topics, and representatives from the

National Park Service, NatureBridge, and Clallam Streamkeepers

shared various outreach tools used by their organizations.

drummers and singers who gave a welcome at both the

presentations and the poster session. Poster presenters shared

research on a variety of topics, and representatives from the

National Park Service, NatureBridge, and Clallam Streamkeepers

shared various outreach tools used by their organizations.

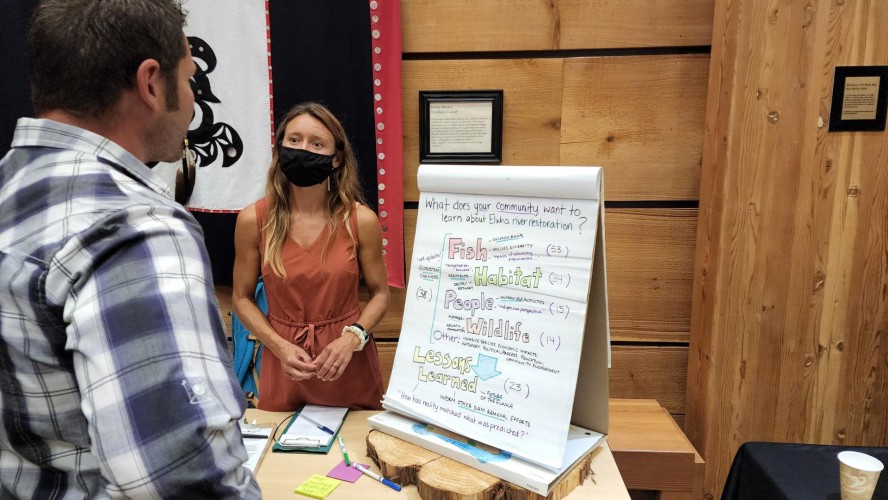

As part of the registration for the public event, we asked if registrants were interested in being involved in science and monitoring on the Elwha; over half said yes. In addition, we have noted that many of the questions currently being answered regarding the river system have been driven by regulations and policy, and the answers are currently driven largely by scientists. So we also asked registrants what questions they have about the Elwha River and its recovery since dam removal. We wanted to know what the community’s interests are in how things are changing, and how those interests align with the science that is happening.

Unsurprisingly, there was a lot of

interest in how the fish have recovered, but there was also

interest in many other aspects of the system (including sediment,

vegetation, and wildlife). Most notably, there was interest in

the human aspects of the dam removals – for example, asking

how human uses of the river and opinions about the dam removal

have changed and how people have benefited from the dam removals.

Unsurprisingly, there was a lot of

interest in how the fish have recovered, but there was also

interest in many other aspects of the system (including sediment,

vegetation, and wildlife). Most notably, there was interest in

the human aspects of the dam removals – for example, asking

how human uses of the river and opinions about the dam removal

have changed and how people have benefited from the dam removals.

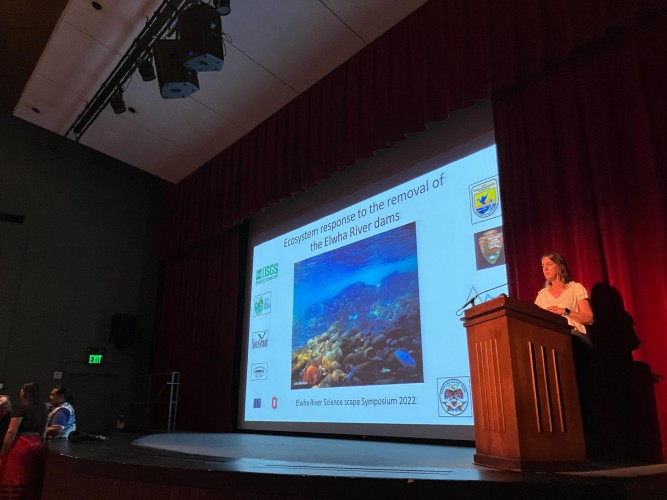

We then attended the three-day

ScienceScape Symposium, hosted at NatureBridge. In addition to

field trips to the Elwha estuary and former Aldwell reservoir,

the occasional swim in Lake Crescent, and an early morning trip

to see Chinook salmon spawning in a nearby stream, we engaged

with the Symposium events in several ways. There were talks

summarizing geomorphological changes, the evolution of vegetation

in the former reservoirs, and the responses of food webs, fish,

and wildlife, and many more talks about individual research

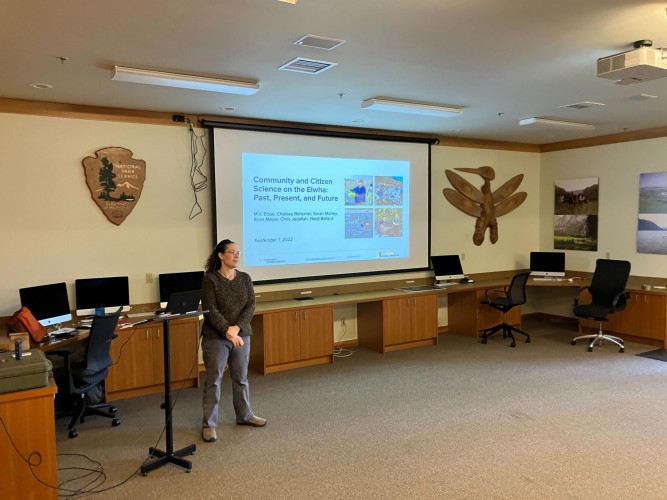

projects on particular topics. We presented insights about the

past, present, and potential future of CCS on the Elwha.

These efforts vary in their past longevity and future

feasibility, often depending on the availability of individuals

who can maintain groups of volunteers and interface with

agencies.

We then attended the three-day

ScienceScape Symposium, hosted at NatureBridge. In addition to

field trips to the Elwha estuary and former Aldwell reservoir,

the occasional swim in Lake Crescent, and an early morning trip

to see Chinook salmon spawning in a nearby stream, we engaged

with the Symposium events in several ways. There were talks

summarizing geomorphological changes, the evolution of vegetation

in the former reservoirs, and the responses of food webs, fish,

and wildlife, and many more talks about individual research

projects on particular topics. We presented insights about the

past, present, and potential future of CCS on the Elwha.

These efforts vary in their past longevity and future

feasibility, often depending on the availability of individuals

who can maintain groups of volunteers and interface with

agencies.

During discipline-specific breakout

groups (paralleling the groups from the April workshop), we heard

CCS mentioned more frequently and confidently as a part of future

plans for Elwha research. There was also strong interest from

scientists in communicating more effectively with the public and

addressing questions about human impacts of the dam

removal.

During discipline-specific breakout

groups (paralleling the groups from the April workshop), we heard

CCS mentioned more frequently and confidently as a part of future

plans for Elwha research. There was also strong interest from

scientists in communicating more effectively with the public and

addressing questions about human impacts of the dam

removal.

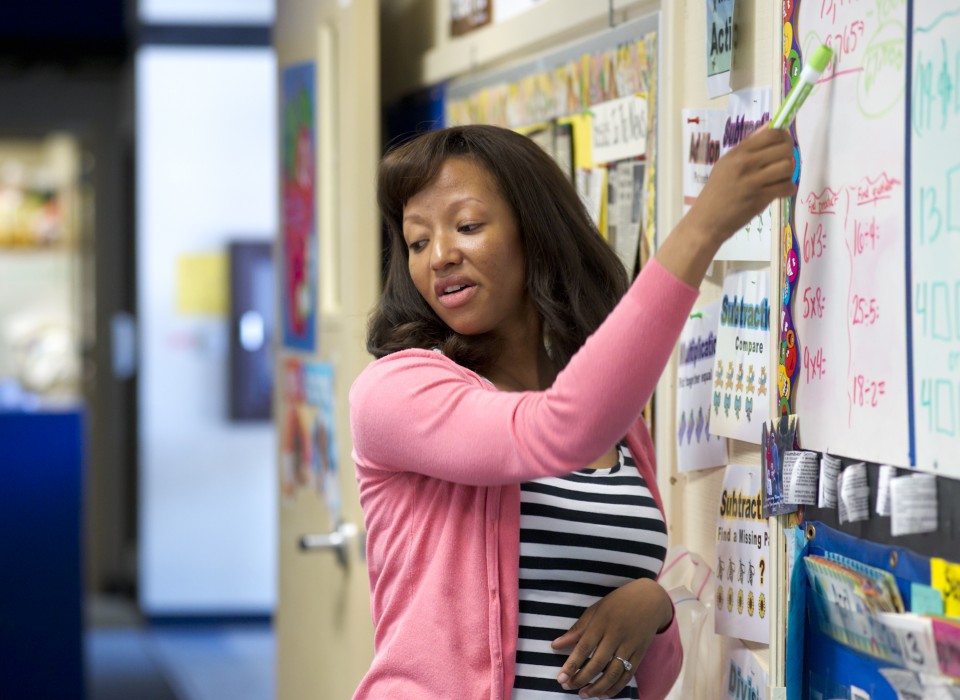

In our breakout session focused specifically on CCS, there was strong interest in working with youth, and in particular with Tribal youth as appropriate. There was potential for connecting with educators in Olympic National Park, programs at Peninsula College, and school programs at NatureBridge.

The future of CCS on the Elwha

We will continue to support existing CCS efforts including water quality measurements, river food web characterization, camera traps for wildlife monitoring, biodiversity observations via iNaturalist, and stable isotope measurements to track the influence of anadromous fish into the watershed. We will also support ScienceScape members in seeking longer-term funding to support CCS and CCS coordination into the future. Future project ideas include remote sensing analysis of vegetation change, birding (with eBird), fish genetics, photo resurveys of geomorphological change, subtidal dive surveys, beach grain size analyses, and back country surveys of a variety of ecological and other processes.

Beyond the many important findings from the past decade of Elwha science, one thing is clear: there are still many fascinating and important questions to be answered about how ecosystems and landscapes respond to a restoration effort at this scale. The ScienceScape meeting afforded many different opportunities to discuss CCS approaches that can sustain and broaden that learning process. We are excited about where this might lead, both for the Elwha, and the broader field of citizen science and watershed restoration.