Using students’ questions in CCS

Submitted by bird on Sun, 09/17/2017 – 3:24pm

When beginning any Citizen Science project, both teachers and students are innately aware that students will collect data to answer scientific questions in which the outcomes are unknown. The whole “without knowing the outcome” part can seem a bit daunting. By opening your class to the authentic scientific questions of a Citizen Science project, you join students on the journey of discovery, becoming just as excited and engaged in the discovery process as they are.

The Next Generation Science Standards (NGSS) scientific practice of Asking Questions and Defining Problems places students at the wheel of their own ship. And, in looking through the progressions of this NGSS practice (APPENDIX E – Progressions Within the Next Generation Science Standards), what becomes clear is that the role of the teacher must become one of facilitator, guiding students to clarify their questions so they can deepen their understanding. How can this be done within a Citizen Science project?

Step One- Begin with an Intriguing Phenomena.

When selecting a Citizen Science project, try to select one that is puzzling enough to pique student curiosity, but is still within the realm of being researched. The goal is for students’ questions to drive instruction, but also allow for data collection and productive inquiry. When you are thinking about jump starting a project, remember that a phenomenon can be a photograph, video or a class experience. It does not need to be an experiment. In my class, students went into our schoolyard and made observations and from their subsequent questions I guided them towards a the Citizen Science project, eBird, a bird monitoring project.

Step Two- Brainstorm Questions.

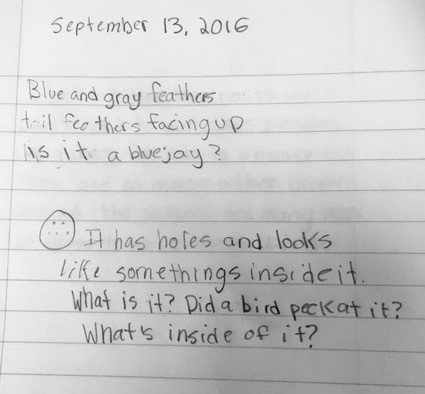

Once your class has observed/experienced a natural phenomenon that will drive their inquiry, ask them to take turns writing down questions with their group. There should be a few discussion protocols put in place before you begin. (1) Go around within your group, taking turns asking a question. (2) Do not stop to discuss the questions. Just write them down. (3) Write down the question exactly as it is asked. The scribe should not edit. (4) It is ok to pass. Keep going around the group until everyone’s questions have been written down. When looking deeply at the world around them, children often have little problem coming up with questions, which is why a Citizen Science project lends itself so easily to the NGSS science practice of Questioning.

Step Three- Rephrase questions as needed.

Ask students to read through their questions, checking to see if their questions are open or closed (yes/no). If they have any closed questions, ask the groups to work together to rewrite them so that they are open-ended.

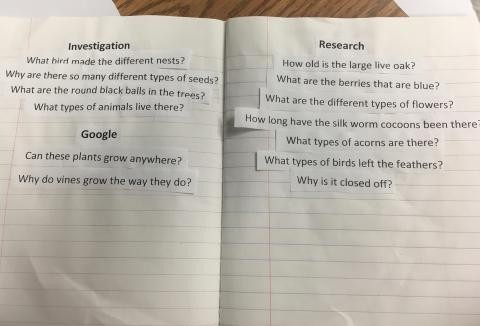

Step Four- Sort your questions.

Once students have edited their questions, have them sort them into different categories. My students love to use color coded Post-It notes for this phase. Sometimes, if they have been generated as a class, I will type them up so that students can cut up the class questions and sort them physically. The goal here is to have my students think deeply about the best way to go about answering their questions, and what the scientific use of their data will be. I have them sort their questions into the following categories:

Googlable: These are questions that may have an answer via a Google search, text resource or other “expert” answer. Here, we will look at obtaining and evaluating information (Where is the best source, and how do we know? etc.). Example googlable question from my class: “At what age do silkworms die?” (students had found old silkworm cocoons from class project while making their outside observations)

Research/Data Collection: These questions require additional information before being answered. For example, one of my students, in making an observation about an oak tree on our playground asked, “What are the black ball things growing off of it?” The student was aware that Google could not directly answer this question because she did not yet have enough information. Questions in this category may also require students to collect data, which may then lead to an investigation, or to more questions. Example researchable question from my class: “What bird made the different nests?” and “what types of birds left the feathers?”

Investigate: These are questions that students use in planning and carrying out their own investigations for their Citizen Science Project (another NGSS science practice). This does not mean that students can ask and answer any question they come up with. In science, limitations of time and other resources must also be taken into consideration. Students should be aware of what resources they have available, how much time they may have, etc. These can all be factored into their design process. When looking at a particular Citizen Science Project, where your data will go, who will use it, how must it be presented/collected must also be taken into consideration. Example investigation question from my class: “How old is the large live oak?” and “Which birds live on our school campus?”

Depending on the questions my students ask, these categories may change. Do not look at these as a set of rules, but as a set of ideas. If students ask questions that cannot be answered based on their own research or investigation, it should be acknowledged that the answer might not be fully realized. It is ok to NOT have all of their questions answered. The purpose of this questioning technique is to demonstrate to students that there are different types of questions and therefore different methods for answering them. With this understanding students are better prepared to take ownership of their own inquiry and ownership of their Citizen Science project.

For additional resources on asking questions, go to: Question Formulation Technique

Peggy Harte has been teaching elementary school for over 20 years. She earned her Bachelors of Arts in 1996 and her Masters in Education in 2005. She now works as the Elementary Science Specialist for all first to sixth graders at her school, where she is conducting a school-wide citizen science project. Her interest in citizen science began with her involvement in a four-year research program through the University of California Davis called iStar (Innovations in STEM Teaching and Research). Outside of the classroom, she enjoys spending time with her two kids running, hiking, kayaking, reading and camping; she also volunteers as a doula at Sutter Davis Hospital.

Tags:

school